Languages

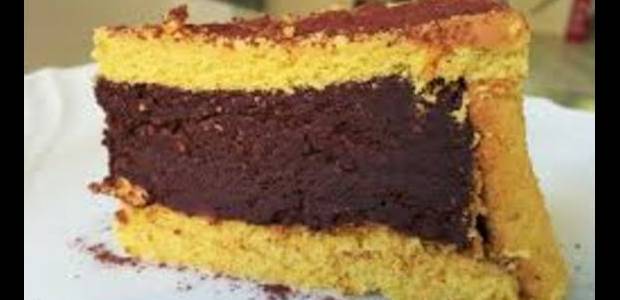

Cacio Bavarese (Bavarian Cheese Dessert)

The Municipality of Langhirano, with the editing of Gabriele Rozzi, has recently published a book of recipes drawn from the cooking notebooks of Emma Agnetti Bizzi, an important langhiranese society’s figurehead of the of the early decades of the twentieth century for her initiatives in the field of assistance (she was president of the Female Mutual Aid Society and promoter of the nursery and shelter for the elderly) and culture (the founder of the local amateur dramatics and animator of the popular library).

The cookbook of Agnetti Bizzi arouses interest as it reflects the characteristics of an early twentieth-century bourgeois cuisine, a cuisine that draws inspiration from the pragmatic school of the people, and from the chefs researches, but is at the same time equidistant from both: a food not so low-profile to fall into vulgarity, but not even so high as to become to close to the refined atmosphere of the high-society mansions. A "modern" cuisine, attentive to the needs of that social class character of the bourgeois century whose periodization, as you know, comes up to the events of World War I and thus encompasses the first decades of the twentieth century, period, as we said, in which the Bizzi Agnetti compiled her culinary notebooks.

We have extrapolated the recipe for Cacio Bavarese (Bavarian Cheese Dessert), a pudding that is prepared like this:

Cooked egg yolks, 8 - sugar, 3 ounces (an ounce is about 27 grams), - fresh butter, 4 ounces - Vanilla, 10 cents

Pound in a mortar the yolks. Then pass a sieve with butter and sugar. Add to the mixture a small glass of liquor at will. Line the mold with wet biscuits in the liqueur. Pour the mixture and put on ice.

As it can be seen it is a simple but tasty preparation which needs, in order to be prepared to the best, of an absolute quality of raw materials: butter and eggs. With regard to the latter it is worth to note that the use of the cooked yolk than raw, certainly more common in today's preparations, was dictated not only by the need to obtain a more dense, but, probably, from hygienic requirements of storage. Another obvious observation: the sweet needs an ice chest in order to be properly cooled, a willingness evidently reserved only to the propertied classes.

The name of the preparation draws the most famous Bavarian cream or bavarois, invented by French pastry chefs at the court of the Wittelsbach, from which, however, is distinguished by the lack of ingredients: cream and the gelatin. But why “cheese”? It is, quite simply, a translation from the French: the Fromage Bavarois is the name under which the cream is mentioned in the nineteenth transalpine recipe (for example in Le Cuisinier Royal Alexandre Viard) bearing in mind that then the term “cheese” was designated for any preparation made from dairy products, among which also the creams made from cream. In short, compared to the much more elaborate recipes of french gourmet’s canon of noble origin, Cacio Bavarese simplifies the most of ingredients and preparation, as befits a kitchen essential, less convoluted, but no less tasty, following the rules of the bourgeois cuisine.

It is worth noting that even Pellegrino Artusi mentions in his recipe the preparation of this plate, although with another name. His recipe is titled Bavarian Lombard and he writes, "you might call the sweet dish of the day as it is often well accepted and used in many families." To be precise, the Artusi's version is much more caloric than the Agnetti Bizzi (180 grams of sugar and the same of butter for six eggs) but both share an area of distribution corresponding to the Bassa Parmense: the land of good milk, good butter, good eggs. Even today those who want to taste the Cacio Bavarese have to orient their research towards the Bassa Parmense lwhere several restaurateurs still offer it (even in the name of Budino del Vescovo: the bishop pudding ) as a worthy end of a meal, perhaps recalling that Giuseppe Verdi as well was an admirer of such specialties.

But, at this point, you might ask, what’s the connection between the Langhiranese Agnetti Bizzi an the Bassa Parmense. The secret is soon out: the father of Agnetti Bizzi, Arturo Agnetti, lived for some years as a medical officer in Monticelli d'Ongina, a country where even Emma married. So our author certainly did not waste the opportunity to insert in his notebooks cooking the delicious desserts so widespread in those regions.

Reading suggestions:

Emma Agnetti Bizzi, Recipes of the early twentieth century, introduction, edition and glossary by Gabriele Rozzi, Langhirano, Municipality of Langhirano, 2016.

La cucina di Verdi. Armonie di note, profumi e sapori sulla tavola del maestro, Milano, Giorgio Mondadori, 2003, p 112.

Published in

The culinary heritage of the past is a mine to be explored for to rediscover the historical foundations of Italian cuisine.

We rediscover, with this column, the deepest roots of our civilization through our cookery.

About the author

Alberto Salarelli

E' ricercatore presso il Dipartimento Lettere, Arti, Storia e Società dell’Università dell’Università degli Studi di Parma.

Oltre ai temi legati alla documentazione in formato digitale, coltiva un particolare interesse per la storia della cultura e della gastronomia, con particolare riferimento alla Pianura Padana; su questo argomento ha pubblicato diversi articoli e monografie.

Scrive per il periodico "MensArte".